Founded in 1951 by Lester Koenig (December 3, 1917 – November 21, 1977), Contemporary Records is a uniquely Hollywood story. An intellectual who loved the arts, Les Koenig (pronounced Kay-nig) fell in love with jazz as an adolescent in New York, where he grew up, the son of a judge. Record collecting led to a lifelong friendship with future music industry icon John Hammond, seven years his senior, who took the young Koenig along to recording sessions he, Hammond, was producing, sparking in Koenig the passion to own a jazz record company one day. In fact, Koenig might not have devoted himself to music as a career had he not, years later, been targeted by political persecution. Read More

Founded in 1951 by Lester Koenig (December 3, 1917 – November 21, 1977), Contemporary Records is a uniquely Hollywood story. An intellectual who loved the arts, Les Koenig (pronounced Kay-nig) fell in love with jazz as an adolescent in New York, where he grew up, the son of a judge. Record collecting led to a lifelong friendship with future music industry icon John Hammond, seven years his senior, who took the young Koenig along to recording sessions he, Hammond, was producing, sparking in Koenig the passion to own a jazz record company one day. In fact, Koenig might not have devoted himself to music as a career had he not, years later, been targeted by political persecution. Read More

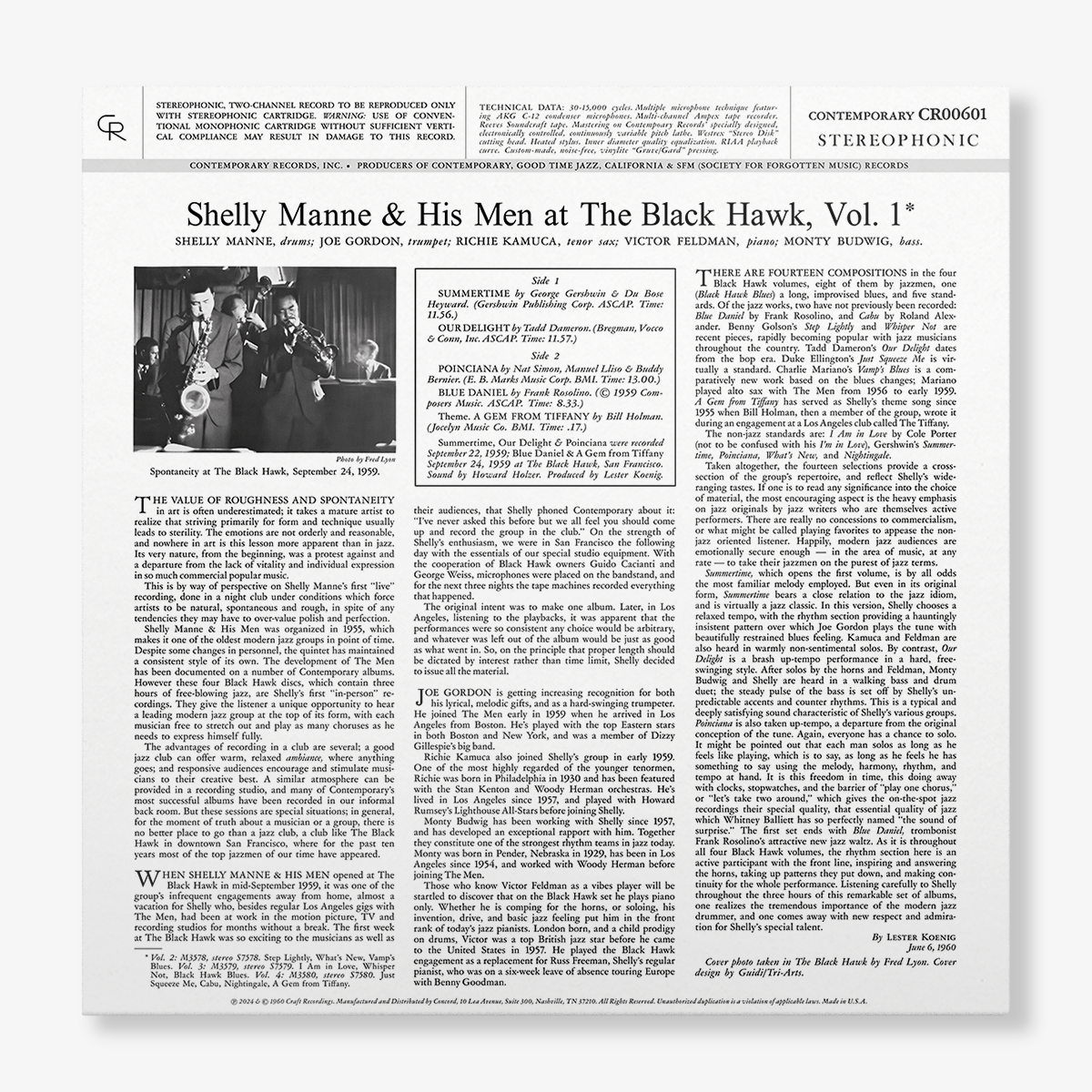

CONTEMPORARY RECORDS

FEATURED ARTISTS

The Contemporary Records Story

Founded in 1951 by Lester Koenig (December 3, 1917 – November 21, 1977), Contemporary Records is a uniquely Hollywood story. An intellectual who loved the arts, Les Koenig (pronounced Kay-nig) fell in love with jazz as an adolescent in New York, where he grew up, the son of a judge. Record collecting led to a lifelong friendship with future music industry icon John Hammond, seven years his senior, who took the young Koenig along to recording sessions he, Hammond, was producing, sparking in Koenig the passion to own a jazz record company one day. In fact, Koenig might not have devoted himself to music as a career had he not, years later, been targeted by political persecution.

At Dartmouth College, among Koenig’s friends was Budd Schulberg whose father, B.P. Schulberg, was the head of production at Paramount Pictures. The elder Schulberg appreciated Koenig’s film and music reviews in the Dartmouth paper and got to know him during family vacations that Koenig spent in California with the Schulberg family.  After a time at Yale Law School, which he left after his father died, Koenig was hired by Martin Block to work at New York radio station, WNEW, on his popular program, Make Believe Ballroom, on which Block played records by dance bands, simulating the ambience of a ballroom to give the illusion that he was broadcasting live concerts. After a year with Block, in 1937 B.P. Schulberg wired Koenig, instructing him to drop everything and come to Hollywood, where Schulberg would set him up as a writer at Paramount.

After a time at Yale Law School, which he left after his father died, Koenig was hired by Martin Block to work at New York radio station, WNEW, on his popular program, Make Believe Ballroom, on which Block played records by dance bands, simulating the ambience of a ballroom to give the illusion that he was broadcasting live concerts. After a year with Block, in 1937 B.P. Schulberg wired Koenig, instructing him to drop everything and come to Hollywood, where Schulberg would set him up as a writer at Paramount.

Koenig was a full-fledged Hollywood screenwriter, but he never abandoned his passion for jazz. He produced sessions (his first) for Jazz Man Records, a record store that also produced recordings. Jazz Man was just down the block from Paramount's main gate on Melrose Avenue and was a regular haunt for Koenig. Koenig befriended the owners of Jazz Man, Marili Morden and her successive husbands, David Stuart and Nesuhi Ertegun, both of whom remained friends and eventually worked together for Koenig at Contemporary. A New Orleans-style jazz revival was emerging in the Bay Area and Koenig helped document the burgeoning movement by financing and producing records beginning in 1941 for the Jazz Man catalog, records by such figures as Lu Watters, Bob Scobey, Turk Murphy and others.

Shortly after the U.S. entered World War II, Koenig joined the Army Air Corp’s film unit, writing scripts for war documentaries. Within a year, in 1943, he was working with director William Wyler, an association that would last nine years. Among Koenig’s wartime output with Wyler was the celebrated script for the documentary The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944), a film that was praised by President Roosevelt after he screened it at the White House. Returning to civilian life as Wyler’s second-in-command, Koenig played key roles on such landmark films as The Best Years of Our Lives (Dana Andrews, Fredric March, Myrna Loy), The Heiress (Olivia de Havilland, Montgomery Clift), Detective Story (Kirk Douglas, Eleanor Parker), Carrie (Laurence Olivier, Jennifer Jones) and Roman Holiday (Audrey Hepburn, Gregory Peck).

Koenig’s life in movies was effectively ended by the Red Scare in 1953, when he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was flayed by the conservative Hollywood establishment for having left-wing sympathies, and blacklisted he turned his attention to music full-time.

Les Koenig had launched Good Time Jazz Records in 1949 as a home for the Jazz Man and Crescent Records catalogs (including titles by New Orleans legends, Bunk Johnson, Kid Ory, George Lewis and Jellyroll Morton), which he had acquired after Ertegun and Morden’s divorce. Among the first new GTJ titles Koenig produced were the first recordings by the Firehouse Five Plus Two (featuring players who had day jobs as senior creatives with Disney), a trad-jazz-based novelty band that enjoyed popularity among A-list Hollywood celebrities of the day. In 1951, Koenig created the Contemporary label, initially as a platform for contemporary classical composers, hence the name, Contemporary.

In 1951, Koenig was approached by former Stan Kenton bassist Howard Rumsey who with his business partner, John Levine, operated the seminal West-Coast jazz venue, the Lighthouse, to undertake the release of the first Lighthouse All-Stars album they had recorded themselves. Koenig did so and transformed Contemporary from a contemporary classical vehicle to a modern jazz label. And with the blacklist, he transformed himself into a full-time jazz label owner.

Contemporary’s records, particularly those recorded by engineer Roy DuNann, have long been prized by audiophiles. Koenig was meticulous about capturing the essence of what musicians were trying to express; that was his primary goal as a producer. Koenig came to appreciate and understand the expressive possibilities of film and audio technology during his movie days when he befriended, among others, the legendary cinematographer, Gregg Toland, who worked on many of Wyler’s pictures and is probably most famous for Citizen Kane. As an early fan of music and records, Koenig was equally fascinated by audio technology.

Contemporary’s early sessions were generally held at Capitol Records, but Koenig did bring his own microphones to those sessions. Determined to set up his own studio, he lured engineer Roy DuNann away from Capitol in 1956. DuNann, who worked at Capitol under the legendary John Palladino, had already made a name for himself, engineering, among others, Tennessee Ernie Ford’s massive number-one hit "Sixteen Tons." DuNann was impressed with Koenig’s attention to detail, as well as his mics. Koenig’s dedication to high-quality audio was particularly important for DuNann, who in short order set about turning the warehouse at the back of Contemporary’s Melrose Place office into a first-rate recording studio. Koenig had already invested in top-line gear. The equipment included several German and Austrian tube condenser microphones including two Neumann U-47s, prized today as the vocal mics of choice by many top recording stars, and a pair of AKG C-12s, the Rolls Royce of microphones. The combination of DuNann’s extraordinary abilities, a large, high-ceilinged live recording room, high-quality gear, a simple, but pristine signal path and first-rate musicians made Contemporary a leader in capturing jazz with unprecedented warmth and immediacy.

The list of important Contemporary engineering alumni includes DuNann, of course, studio designer Howard Holzer and the preeminent mastering engineer, Bernie Grundman, who came to Contemporary as a young engineer and who was taught the intricacies of disc mastering by Les Koenig in Contemporary’s state-of-the-art mastering studio, as was Les Koenig’s son, John, who later became Contemporary Records’ president when Les Koenig died at 59 in 1977. Among fans of Les Koenig’s producing and his audio engineering methods were Herb Alpert and Jac Holzman (founder of Elektra records), both of whom sought out Koenig to master their own records in the early days of both of their labels, an assignment Koenig would delegate to Grundman, who eventually went to work for Alpert at A&M Records before starting his own world-class state-of-the-art mastering facility.

Les Koenig was known for his respect for and friendship with musicians, as well as his refreshingly honest business practices. These qualities made Contemporary a favored destination among artists. While the label’s early identity was shaped by Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars, a group made up mainly of Kenton alumni. Kenton alumni who participated in Contemporary sessions from the outset included Shelly Manne, Art Pepper, Bob Cooper, Shorty Rogers, Conte Candoli, Bud Shank and many others. Their sound was emblematic of West Coast jazz of the day, but Koenig, a New Yorker, was not committed only to recording local musicians.

The Contemporary catalog is filled with important efforts by Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Benny Golson, Art Farmer, Phineas Newborn, Benny Carter, Helen Humes, the Curtis Counce Group, Victor Feldman, Harold Land, Teddy Edwards, Howard McGhee, Ben Webster, Woody Shaw along with West-Coasters Hampton Hawes, Barney Kessel and Andre Previn. After Les Koenig’s death, during his seven-year tenure at the helm of Contemporary, John Koenig, who had produced records with his father for several years including several with Art Pepper (with Elvin Jones and also with Charlie Haden), Art Farmer (with Art Pepper, Hampton Hawes, Shelly Manne and Ray Brown), Woody Shaw, Sonny Simmons and others), produced albums by Joe Henderson (with Chick Corea), Joe Farrell (with Freddie Hubbard), Bobby Hutcherson (with McCoy Tyner), Chico Freeman (with Wynton Marsalis and Bobby Hutcherson), George Cables (with Bobby Hutcherson and Freddie Hubbard), Peter Erskine (with Michael Brecker, Kenny Kirkland and Eddie Gomez) and others, adding new dimension to Contemporary’s catalog. The artists whom Lester and John Koenig recorded responded to their steadfast faith in their creativity, as well as their own musical bona fides. Consequently, Contemporary became an essential vehicle for them.

Seven decades after its inception, the label’s legacy looks more imposing than ever, as the albums — many of them now widely heralded as classics — continue to inspire fans of jazz and audio and serve as an influence and inspiration for leading players on the contemporary scene.